Tom Young is no stranger to Lebanon. Having spent more than a decade living and working in Beirut, the respected British artist has developed a deep emotional connection to the country. We learn more about his journey through his incredibly moving and inspiring works of art.

What brought you to Lebanon?

What brought you to Lebanon?

I have lived in Lebanon for eleven years. My first trip to Lebanon was in spring 2006 to do a commissioned landscape for my Lebanese car mechanic in London, Raed Zahraddine, who loved my paintings and wanted a painting of his home village Ain Anoub near Bechamoun. Having returned to do art workshops for children after the 2006 war, and then to paint in 2007 and 2008, I eventually moved to live in Lebanon in 2009 after the gallerist Aida Cherfan invited me to do an exhibition in Beirut.

I felt at home immediately and had a strong sensation that I had been here before. Somehow I already knew my way around. Having watched many news reports about the civil war, which were broadcast on British television almost every day when I was growing up, Lebanon had already been in my consciousness at a particularly tragic time in my own life; when I was 10, my mother died in traumatic circumstances, and we had suddenly moved away from my beloved childhood home. Then my grandfather and cat died shortly afterwards.

Why do you feel so attached to the country?

In Lebanon, I felt immediately understood and recognized — as if my memory of pain, loss and displacement had also been experienced by most Lebanese in a way that very few people in my own country had experienced. This is an emotional connection which transcends national identity. I see myself reflected in the scarred walls of the city and empty abandoned mansions. I aim to do what I can to give them life. I admire the resilience and spirit of people in Lebanon to recover from tragedy, and recognize something very familiar about that. And of course, there’s the kindness and generosity of people in Lebanon, the joy and celebration, music, art, delicious food and wine, the rich variety of beautiful landscapes and historic sites. There is a vibrant energy here which inspires me to paint unlike anywhere else in the world, and also an urgency to capture things before they go. For it is a place of transience and perpetual change. It is under threat from aggressive neighbors and self-serving local politicians. This unique treasure of culture and creativity must be valued and supported —now more than ever.

Martyrs’ Square Night

Just a few days after the main protest site in Martyrs’ Square had been vandalized by thugs in November 2019, I was amazed to see everything had been repaired and a huge celebration was held in the main square with music and dancing. Inspired by this stunning expression of unity, joy and resilience — to come back stronger and create a better Lebanon for all of its citizens. I painted this picture of the overall scene, paying close attention to the mosque and church, the moon and stars that were shining in the sky that night and the little “aranees” stall in the foreground — symbolizing the ordinary worker and a classic Lebanese tradition. “Aranees” is for everyone — regardless of religion!

Just a few days after the main protest site in Martyrs’ Square had been vandalized by thugs in November 2019, I was amazed to see everything had been repaired and a huge celebration was held in the main square with music and dancing. Inspired by this stunning expression of unity, joy and resilience — to come back stronger and create a better Lebanon for all of its citizens. I painted this picture of the overall scene, paying close attention to the mosque and church, the moon and stars that were shining in the sky that night and the little “aranees” stall in the foreground — symbolizing the ordinary worker and a classic Lebanese tradition. “Aranees” is for everyone — regardless of religion!

Bosta

The classic symbol of Lebanese youth, the school bus is the traditional mode of public transport for children in Lebanon. But it is also the symbol of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, after the conflict was sparked off by a bus shooting in Ain El Remaineh on 13 April 1975. Many of the leaders from that conflict are still in power today, and the hopelessly dysfunctional system of sectarianism which they represent is what many people in Lebanon are trying to change now.

The classic symbol of Lebanese youth, the school bus is the traditional mode of public transport for children in Lebanon. But it is also the symbol of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, after the conflict was sparked off by a bus shooting in Ain El Remaineh on 13 April 1975. Many of the leaders from that conflict are still in power today, and the hopelessly dysfunctional system of sectarianism which they represent is what many people in Lebanon are trying to change now.

In October 2019 in Martyrs’ Square, I saw a crowd of young men riding a “bosta” painted in the colors of Lebanon. The sense of joy and celebration was inspiring, as was their extreme risk taking! I decided to paint this and release the image for Lebanese Independence Day on 22 November. As I was finishing the painting that morning, I saw that thugs were vandalizing the main protest site in Martyrs’ Square again and burning the “thawra” fist. Seeing this gave me greater conviction that I had to finish the painting and send it out on social media as a show of solidarity and resilience that no one can destroy the momentum and spirit which the ‘bosta‘ represents.

Asphyxiated City (Night)

We are all interconnected by a digital matrix like never before. Seen from a distance, Beirut is an endless labyrinth of concrete: one of the most densely populated cities in the world. From a distance, the concrete jungle of South Beirut has an awesome and shocking beauty. All those lives, all those stories, all those families — it is the modern maze, what human development looks like when there is no urban planning or overall design: anarchic growth in concrete form. When there are fireworks, one is never sure — particularly now after the devastating explosion in August 2020 — whether it is a party, a wedding, a speech by a certain political leader, a tragic accident or a sinister attack. Lebanon is a paradox of heaven and hell. As I was painting the picture, I laid the canvas flat on the floor of my studio; wet paint settled on the canvas spontaneously and created the figure of an angel or wizard flying over the urban scene. Painting is so often about harnessing “accident.”

We are all interconnected by a digital matrix like never before. Seen from a distance, Beirut is an endless labyrinth of concrete: one of the most densely populated cities in the world. From a distance, the concrete jungle of South Beirut has an awesome and shocking beauty. All those lives, all those stories, all those families — it is the modern maze, what human development looks like when there is no urban planning or overall design: anarchic growth in concrete form. When there are fireworks, one is never sure — particularly now after the devastating explosion in August 2020 — whether it is a party, a wedding, a speech by a certain political leader, a tragic accident or a sinister attack. Lebanon is a paradox of heaven and hell. As I was painting the picture, I laid the canvas flat on the floor of my studio; wet paint settled on the canvas spontaneously and created the figure of an angel or wizard flying over the urban scene. Painting is so often about harnessing “accident.”

Babel

The city is a vast mosaic of concrete, one block piled on top of another. Gleaming towers for the elite rise into the sky, beyond reach for most people. The inequality of human societies all over the world is amplified in Beirut: the city of extremes. Yet however shocking the dizzying density of our concrete mess may be, it is illuminated by breathtaking Mediterranean light, glowing with misty beauty.

The city is a vast mosaic of concrete, one block piled on top of another. Gleaming towers for the elite rise into the sky, beyond reach for most people. The inequality of human societies all over the world is amplified in Beirut: the city of extremes. Yet however shocking the dizzying density of our concrete mess may be, it is illuminated by breathtaking Mediterranean light, glowing with misty beauty.

City Bloom

Flowers bloom and butterflies (all indigenous to Lebanon) fly against the backdrop of a toxic city. Somehow the spirit of beauty survives despite the brutal onslaught of modern urban development; life thrives in the cracks. New hope rises after the storm.

Flowers bloom and butterflies (all indigenous to Lebanon) fly against the backdrop of a toxic city. Somehow the spirit of beauty survives despite the brutal onslaught of modern urban development; life thrives in the cracks. New hope rises after the storm.

Corniche (Edge of the World)

During the coronavirus lockdown (perhaps just the first), I walked along the empty Corniche seafront. It was so peaceful, yet something was not right. It was once full of people enjoying a stroll in Beirut’s only viable public place, where families have picnics alongside joggers, fishermen, people relaxing and smoking shisha as they enjoy the sea view. They’ve vanished; and not only the people, but also the traffic. No cars. It feels like the edge of the world. CCTV cameras cast their electronic gaze from high above, surveying the ghostly scene; or do they? Perhaps they don’t work anymore. These dormant instruments of surveillance stand next to the self-orientalized fantasy of palm trees artificially imported from Arabia after the civil war ended, replacing the original indigenous tamarisk and oleander trees which used to grow there.

During the coronavirus lockdown (perhaps just the first), I walked along the empty Corniche seafront. It was so peaceful, yet something was not right. It was once full of people enjoying a stroll in Beirut’s only viable public place, where families have picnics alongside joggers, fishermen, people relaxing and smoking shisha as they enjoy the sea view. They’ve vanished; and not only the people, but also the traffic. No cars. It feels like the edge of the world. CCTV cameras cast their electronic gaze from high above, surveying the ghostly scene; or do they? Perhaps they don’t work anymore. These dormant instruments of surveillance stand next to the self-orientalized fantasy of palm trees artificially imported from Arabia after the civil war ended, replacing the original indigenous tamarisk and oleander trees which used to grow there.

Desolation (Ground Zero Beirut)

Melancholy figures survey a scene of shocking devastation after the port explosion on 4 August 2020: an apocalypse. Heavenly light fills the ghostly scene in a sense of spirituality; for the souls of those who lost their lives are somewhere else. A group on the left comfort each other; for scenes of compassion and kindness are as much a part of this tragic event as anger and grief. A young boy stands alone, his body rigid with shock, unable to comprehend what he sees or what has happened. What kind of childhood is this? What kind of world do those murderous leaders who avoid responsibility and justice think they are creating for our children and grandchildren? Do they care?

Melancholy figures survey a scene of shocking devastation after the port explosion on 4 August 2020: an apocalypse. Heavenly light fills the ghostly scene in a sense of spirituality; for the souls of those who lost their lives are somewhere else. A group on the left comfort each other; for scenes of compassion and kindness are as much a part of this tragic event as anger and grief. A young boy stands alone, his body rigid with shock, unable to comprehend what he sees or what has happened. What kind of childhood is this? What kind of world do those murderous leaders who avoid responsibility and justice think they are creating for our children and grandchildren? Do they care?

Paradiso Dream

Villa Paradiso, a beautiful house in Gemmayzeh which lies somewhere between our reality and a heavenly dream, glimpsed at through pink bougainvillea. It had been the residence of the Baloumian family for many years before they fled the house in haste at the beginning of the Lebanese war in the late 1970s. The family patriarch Mardiros had made a miraculous escape from the Armenian Genocide in 1915 before arriving in Lebanon. They left most of their belongings — books, articles, testimonies, family photograph albums, perfumes, an Armenian typewriter — where they remained untouched for 35 years until Remi Feghali discovered them after his family had bought the house in 2010. Remi began a partial renovation of the derelict house, and then I came across the building and worked with him to transform the house into a venue for an exhibition in 2013, in which I paid tribute to the remarkable story of the Baloumian family. The house subsequently became a cultural venue for many other artists from 2013-2016. The former EU Ambassador to Lebanon Christina Lassen visited one of the exhibitions, fell in love with the house and decided it should be the official residence of the European Union ambassadors to Lebanon — which it is to this day. It was damaged in the explosion in August 2020 but has been completely repaired and renovated.

Villa Paradiso, a beautiful house in Gemmayzeh which lies somewhere between our reality and a heavenly dream, glimpsed at through pink bougainvillea. It had been the residence of the Baloumian family for many years before they fled the house in haste at the beginning of the Lebanese war in the late 1970s. The family patriarch Mardiros had made a miraculous escape from the Armenian Genocide in 1915 before arriving in Lebanon. They left most of their belongings — books, articles, testimonies, family photograph albums, perfumes, an Armenian typewriter — where they remained untouched for 35 years until Remi Feghali discovered them after his family had bought the house in 2010. Remi began a partial renovation of the derelict house, and then I came across the building and worked with him to transform the house into a venue for an exhibition in 2013, in which I paid tribute to the remarkable story of the Baloumian family. The house subsequently became a cultural venue for many other artists from 2013-2016. The former EU Ambassador to Lebanon Christina Lassen visited one of the exhibitions, fell in love with the house and decided it should be the official residence of the European Union ambassadors to Lebanon — which it is to this day. It was damaged in the explosion in August 2020 but has been completely repaired and renovated.

Rose Interior

The Rose House in Manara, Ras Beirut, boasts a magnificent interior. Fayza El Khazen and her family had lived in the house, filling it with exquisite beauty and artistic expression for 50 years (from 1964 to 2014), until she had to leave after her mother Margot died in 2012 and the house was bought by property developer Hicham Jaroudi. It was the end of an era, the passing of a great age. Directly after El Khazen left in 2014, Jaroudi gave me permission to transform the house into an exhibition venue for my art, as well as a place for theater and musical events. Since 2015, it has remained empty and derelict, while many of its windows, doors and shutters have been left to the elements and vandalized. There are plans to secure and renovate the mansion, but nothing has been done to date. Those who care about Beirut’s precious heritage are watching closely.

The Rose House in Manara, Ras Beirut, boasts a magnificent interior. Fayza El Khazen and her family had lived in the house, filling it with exquisite beauty and artistic expression for 50 years (from 1964 to 2014), until she had to leave after her mother Margot died in 2012 and the house was bought by property developer Hicham Jaroudi. It was the end of an era, the passing of a great age. Directly after El Khazen left in 2014, Jaroudi gave me permission to transform the house into an exhibition venue for my art, as well as a place for theater and musical events. Since 2015, it has remained empty and derelict, while many of its windows, doors and shutters have been left to the elements and vandalized. There are plans to secure and renovate the mansion, but nothing has been done to date. Those who care about Beirut’s precious heritage are watching closely.

Survival

A beautiful mansion in Zarif is a symbol of survival from an earlier age as the modern city surrounds it. The house was the residence of British ambassadors from 1941 to 1985. The first diplomat to live there was General Sir Edward Spears from 1941 to 1944, and the main street near the house is named after him — Rue Spears. He played a pivotal role in helping Lebanon become an “independent” state in November 22 1943. During this time, the house hosted many important meetings with leading Lebanese independence leaders such as Riad El Solh, Bechara El Khoury, Adel Osseiran and Camille Chamoun, and French leaders General Catroux and Jean Helleu, and even secret assignations between Spears and the singer Asmahan and society lady Maud Fargeallah. When fighting intensified during the civil war, the British were forced to leave the building. It became a battleground for some months until it was taken over by Dar Al Aytam Al Islamiyeh after their main premises in Aramoun, south of Beirut, was bombed by the Israelis in 1982. Since the house has been in their possession, it has been carefully restored and preserved, and is now an administration center for the Social Welfare Institution. It is a gem in a once glorious part of Beirut, which used to be full of splendid mansions. It is the only one left in the neighborhood. I taught children from Dar Al Aytam in 2016 and 2017, and we transformed it into a publicly accessible art exhibition venue in April 2017.

A beautiful mansion in Zarif is a symbol of survival from an earlier age as the modern city surrounds it. The house was the residence of British ambassadors from 1941 to 1985. The first diplomat to live there was General Sir Edward Spears from 1941 to 1944, and the main street near the house is named after him — Rue Spears. He played a pivotal role in helping Lebanon become an “independent” state in November 22 1943. During this time, the house hosted many important meetings with leading Lebanese independence leaders such as Riad El Solh, Bechara El Khoury, Adel Osseiran and Camille Chamoun, and French leaders General Catroux and Jean Helleu, and even secret assignations between Spears and the singer Asmahan and society lady Maud Fargeallah. When fighting intensified during the civil war, the British were forced to leave the building. It became a battleground for some months until it was taken over by Dar Al Aytam Al Islamiyeh after their main premises in Aramoun, south of Beirut, was bombed by the Israelis in 1982. Since the house has been in their possession, it has been carefully restored and preserved, and is now an administration center for the Social Welfare Institution. It is a gem in a once glorious part of Beirut, which used to be full of splendid mansions. It is the only one left in the neighborhood. I taught children from Dar Al Aytam in 2016 and 2017, and we transformed it into a publicly accessible art exhibition venue in April 2017.

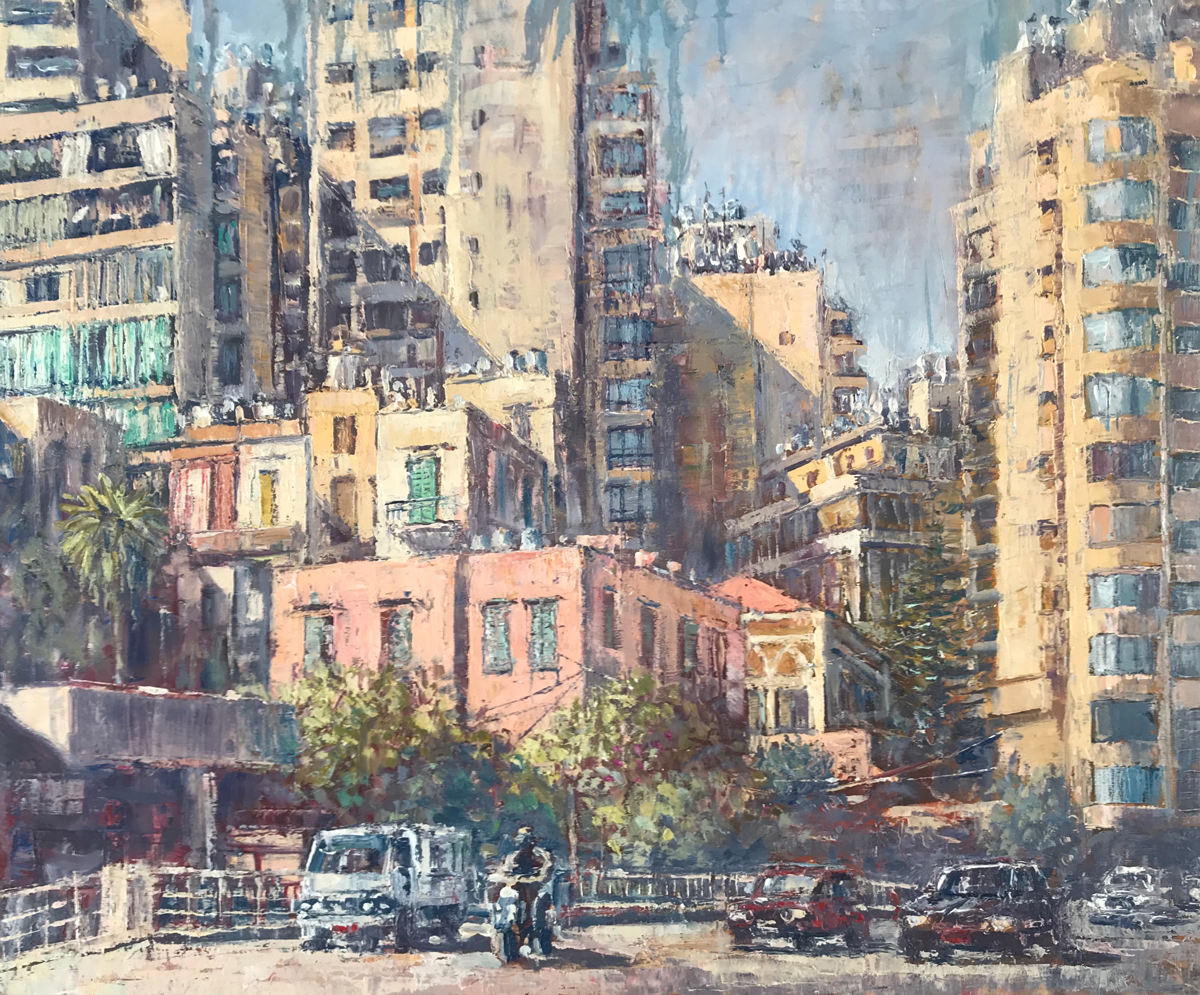

Zuqaq el Blatt

A classic Beirut scene: layers of the city, different eras and styles of architecture piled on top of each other haphazardly as traffic roars past. It buzzes with life and vitality.

A classic Beirut scene: layers of the city, different eras and styles of architecture piled on top of each other haphazardly as traffic roars past. It buzzes with life and vitality.

Starry Night

Every night during coronavirus lockdown in 2020, I saw the same distant figures looking out from their balconies — glimpses of urban melancholy, hoping for better news. Occasionally the city rang with the sound of banging pots and pans to honor heroic doctors and medical workers on the front line. A few months ago, the same sound used to ring out over Beirut at 8pm every night: the sound of protest and demands for political change and basic human rights. I look from my terrace over the urban rooftops to Martyrs’ Square, still lit up by flickering advertising screens that no one can see anymore, selling products that fewer people can buy. Huge cranes lie dormant while the city holds its breath. When shall we be free again?

Every night during coronavirus lockdown in 2020, I saw the same distant figures looking out from their balconies — glimpses of urban melancholy, hoping for better news. Occasionally the city rang with the sound of banging pots and pans to honor heroic doctors and medical workers on the front line. A few months ago, the same sound used to ring out over Beirut at 8pm every night: the sound of protest and demands for political change and basic human rights. I look from my terrace over the urban rooftops to Martyrs’ Square, still lit up by flickering advertising screens that no one can see anymore, selling products that fewer people can buy. Huge cranes lie dormant while the city holds its breath. When shall we be free again?

Angels

In the days following the port explosion, I was inspired by the solidarity and heroism of young people on the streets clearing up the damage. Their spirit of generosity and courage is amazing, and gives us hope for the future. This is the real Lebanon.

In the days following the port explosion, I was inspired by the solidarity and heroism of young people on the streets clearing up the damage. Their spirit of generosity and courage is amazing, and gives us hope for the future. This is the real Lebanon.